Computers finally acting like computers

A lot has been said about modern AI. In my opinion, computers are finally starting to behave like the computers we were promised by science fiction for decades.

As a child of the '70s, computers were magical tools of power and creativity, at least as I saw them on TV. With the first personal computers out in the '80s, it became clear that actually using computers to achieve anything was a difficult mission, something that would take a person years of experience.

I didn't mind that too much. The complexity and rigidity of programming gave me a passion to pursue and job security. This also gave me pride, an identity, and the power to create things that millions of people have used at some point and (hopefully) enjoyed, mostly in the form of video games.

Not just code

When it comes to completing and publishing a piece of software, the work doesn't stop with the code written. There are many other aspects that take time and effort, and that can make the difference between completing a new feature and giving up because of the time investment required.

For example, updating a game to work with the latest SDK, writing copy for a product in multiple languages, digging through crash dumps to find a nasty bug that is accumulating bad user reviews by the hour. These are all tasks that can make a big difference in a product's success, and for which AI can be of great help.

Modern LLMs, when used in an agentic framework such as OpenAI's Codex or Claude Code, can help with many of those tasks. I've been doing this for a while now, and it's a great relief to be able to delegate some of the more tedious tasks to an AI assistant, including work that requires operating in a web browser !

Sometimes this can save days of clerical work and enable one to focus on the more creative and rewarding aspects of software development, or project development in general.

Coding what, anyway?

To me, writing code is similar to knowing a human language: it's a basic skill that many can obtain to a decent enough level. To code is to implement something, which can be bland and formulaic, or can be innovative and exciting.

I don't think of my job/passion as programming, but more as research & development. There's what I put down in code at runtime, but there's also the research that goes with it, which is often the more meaningful portion of the task.

Usually, if I'm not learning something new, in a new project, something that I can see becoming useful again in the future, then I don't feel like I'm making good use of my time.

For this reason, I always thought that the phrase "learn to code" was silly and shortsighted. To me, that advice sounds like "learn to read and write", which is relatively trivial.

Why it's not stopping

I see AI pessimists as people who land on a planet, find a life form, and start to criticize it because it can't play the piano.

The excitement of someday finding alien life forms isn't about the specific characteristics of that life form, but about the implications of its existence: that life is not unique to Earth, and that the universe is probably teeming with life forms of all kinds.

Today we know that intelligence can be created artificially, and that it's not a unique property of humans or animals. We're doing this digitally, an approach that can require more power than biological intelligence, but that opens the door to rapid improvement, because the rigor of digital logic allows us to use math and simulation to scale in ways that biology cannot.

For the past three years, LLMs have been improving at an incredible pace. GPT-3.5, while impressive, struggled to produce 100 lines of functioning code. GPT-5.2 in Codex can tackle just about anything an experienced programmer can do in virtually any field. More importantly, progress continues at a rapid pace, with new very capable open source models appearing every month, highlighting that AI isn't a fluke; it's a new reality moving forward.

I could write a lot more about the pessimists about AI today, but given the current speed of progress, I think that soon enough, the capabilities are going to be self-evident for everyone. Of course, there will always be those who can live in denial, but that's a statistical necessity when humans are involved.

The good old times

We all have an era that we nostalgically remember as the good old times. The truth is that for the most part, we idealize that era, both due to selective memory and with the benefit of hindsight, which tells us that we could probably go back and truly appreciate it more and leverage it better (true only with a time machine).

Was it better before cellphones, before smartphones, before the Internet ? In some ways, yes, and for some people definitely yes. But if you're hungry for knowledge and ache to create, to build something new every day, then it's hard to lock into a specific technology era and be satisfied with it, no matter the nostalgia factor.

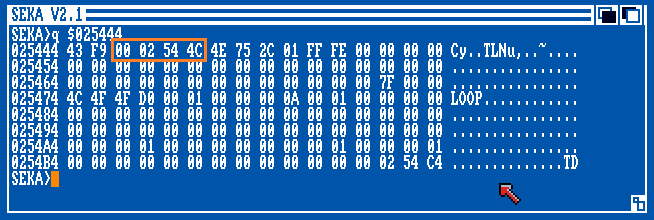

However, I'll play the devil's advocate here and say that from the perspective of a human programmer, the 16-bit era (with 24/32-bit addressing) was probably a sweet spot, not because technology was better, but because it was limited enough to fit in a human brain. On the Amiga, I could visually scroll through all the system memory, and see every piece of code, graphics, and sound data without getting completely lost. The same goes for pixel art, where one can mentally account for every single pixel in a sprite. This kind of simplification, on some level, feels comfortable to the human mind.

For this reason, I think that retro-coding and pixel art will always have a place in the hearts of humans, as something that we're able to create, fully comprehend and feel relaxed about.

Conclusion

I struggled a lot to write this post, which was meant to be written many months ago, with totally different content. As days and weeks went by, technology continued to improve in real-time, and I kept having to partially re-evaluate what I wanted to say. Initially, last year, I was writing a post on how I navigate through Vim using tabs and splits... but my work environment has been changing every 2-3 months. I've been using Visual Studio Code a lot and only recently moved back to tmux, Neovim, and OpenAI's Codex.

Some things are changing for good, some things are coming back. It'll be interesting to see when the dust will settle. For now, the situation continues to be very dynamic, in part due to advances of AI models, in part due to programmers catching up to potential that has been around for a year or so, which in pre-AI times is 7 years, or something.