Blog Posts

Misplaced Pessimism about AI

August 1, 2024

AI beyond the hype

May 12, 2024

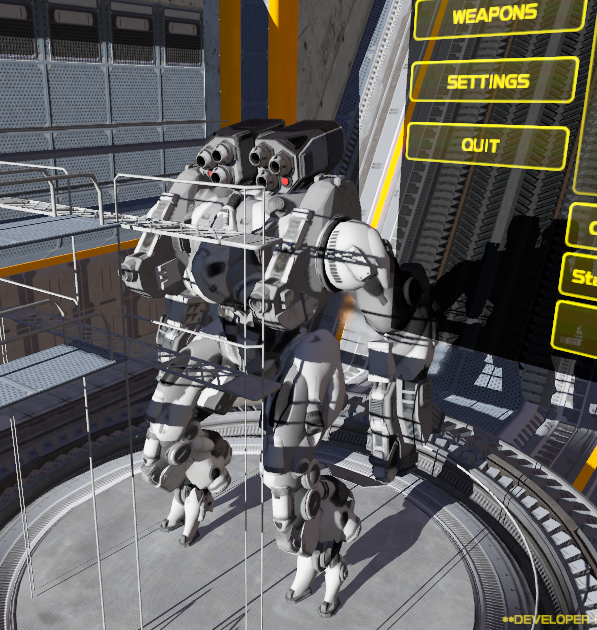

ENZO-TS 2024/Q1 update

May 11, 2024

The irony of LLM hallucinations

September 15, 2023

Computer code, probably instrumental for AGI

July 22, 2023

A definition of reality

July 3, 2022

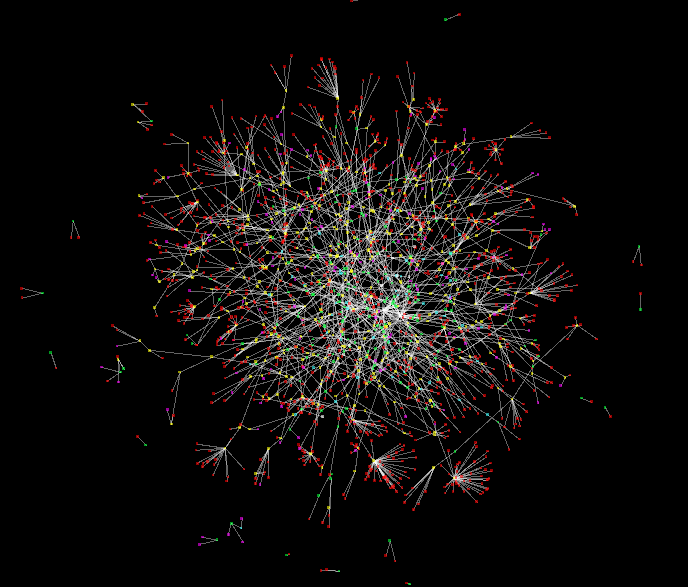

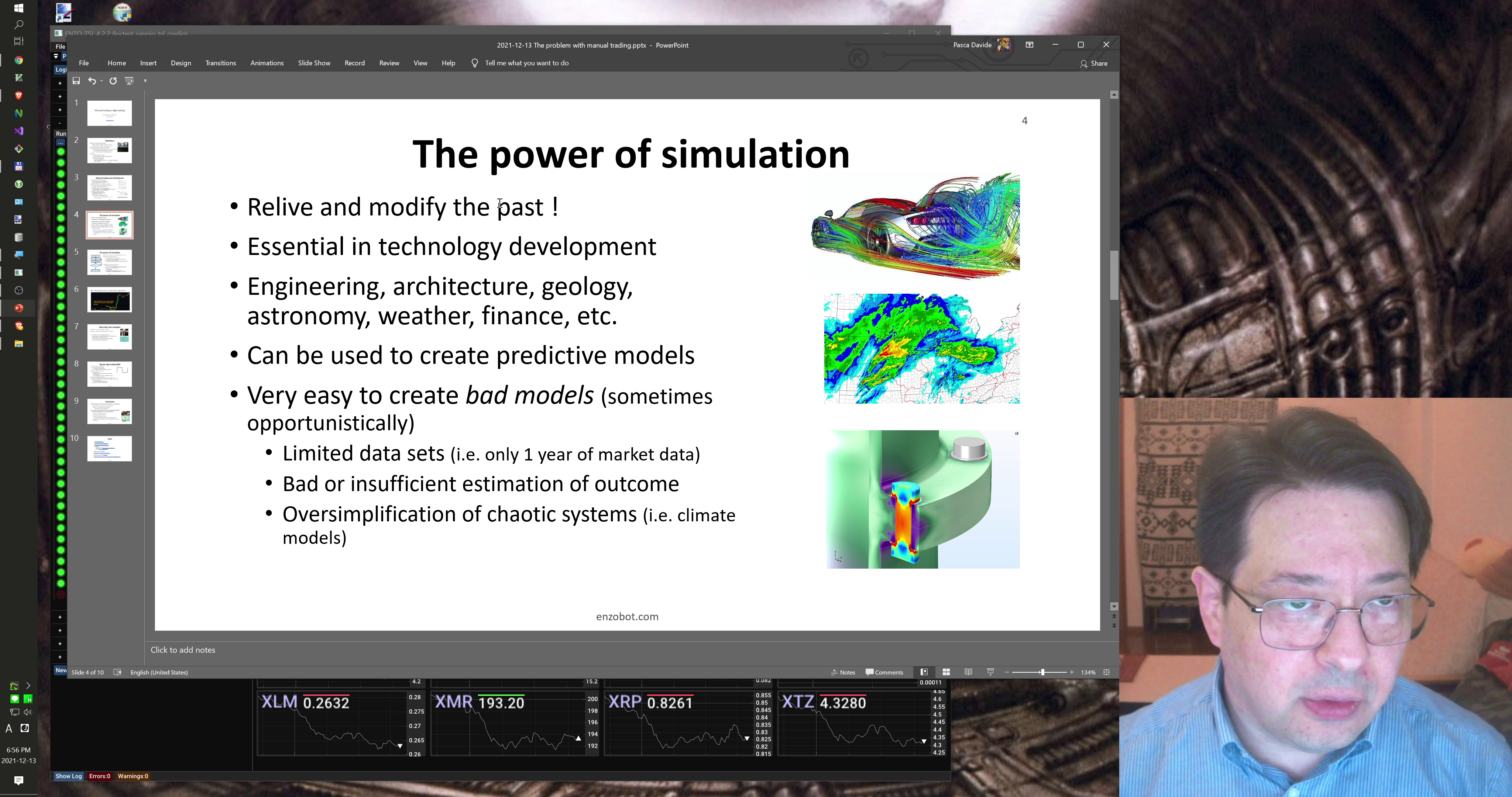

Simulation: from weapon systems to trading

June 8, 2022

Women and children

May 26, 2022

An actual phobia, for a change

April 22, 2022

What's your vote really worth ?

April 7, 2022

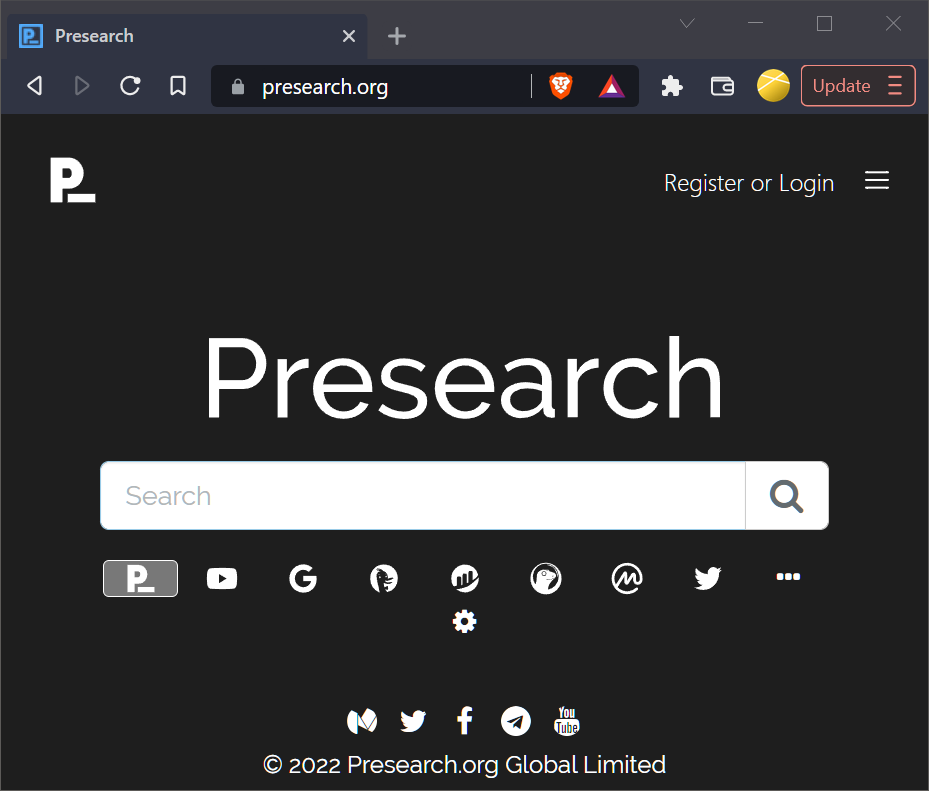

DuckDuckGo cheated on me. I'm now dating Presearch

March 31, 2022

On the Moon landing

March 27, 2022

Happily ever after

March 3, 2022

Monkeys with lipstick

January 7, 2022

Next level thinking ?

January 1, 2022

On Deboonkers

December 30, 2021

The explosive "boredom" problem of civilized societies

December 25, 2021

You are probably being simulated, to some degree

December 16, 2021

Kibun Tenkan, VR edition

December 10, 2021

Mass formations and loss of freedom

December 3, 2021

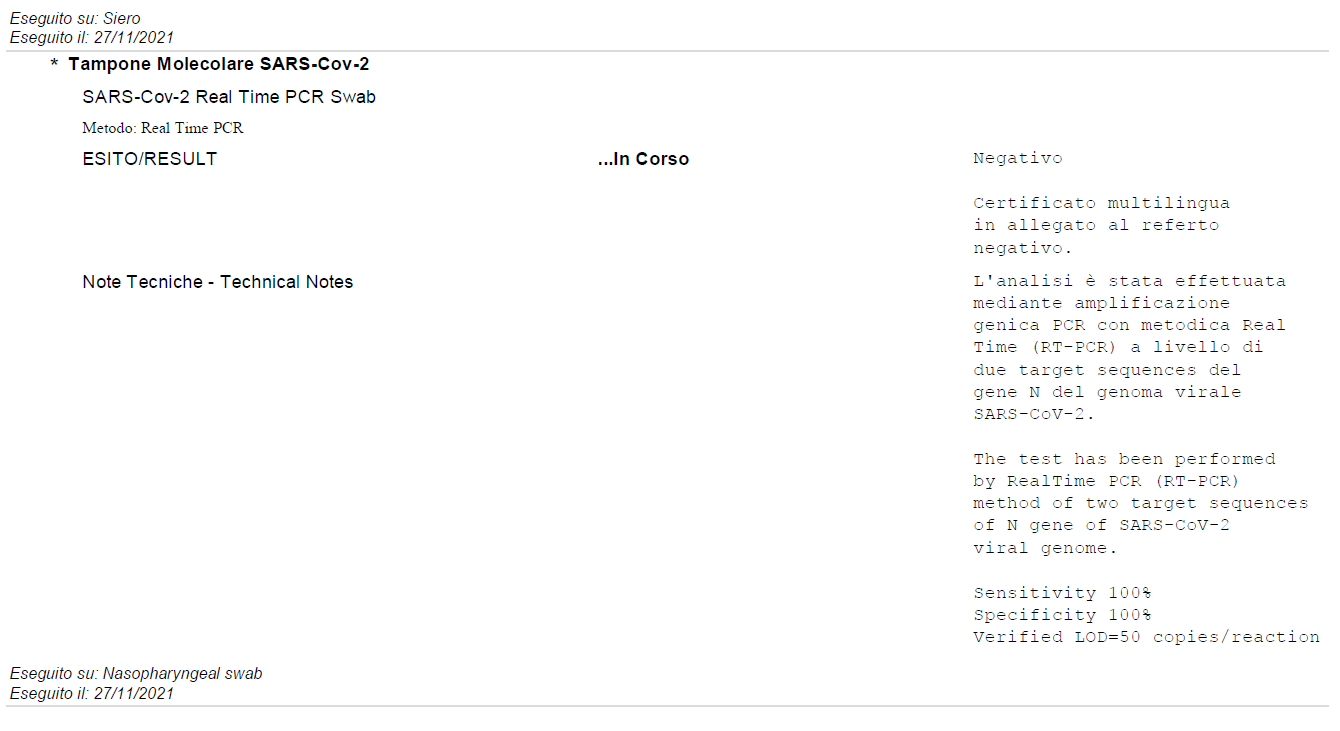

Tokyo-Roma, andata e ritorno (2021/11)

December 1, 2021

The biggest question

October 15, 2021

Shameful death for the non-compliant

October 12, 2021

Adopt a conspiracy theorist

July 18, 2021

Brains to computers, not happening

May 12, 2021

The "rich enough" fallacy

May 6, 2021

Anti-socials

May 4, 2021

Hypnotized emotional beings

May 2, 2021

Teach a dog to wear its muzzle

March 20, 2021

Seek financial independence

February 20, 2021

Truth and reality

January 18, 2021

The take-profit fallacy

January 17, 2021

Digital Perspective

January 13, 2021

My Space !

January 8, 2021

The state of the F-35 sim project

April 11, 2018

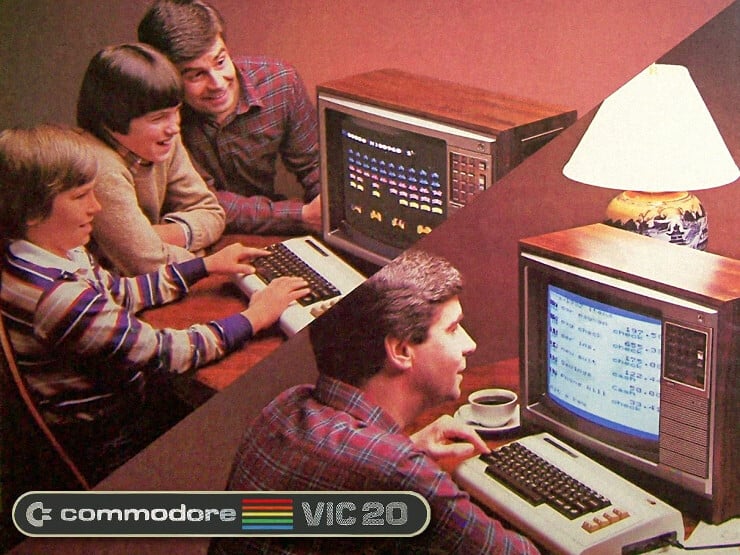

From arcade to simulation (gunning for the F-35)

March 31, 2018

Avionics' improvements

November 29, 2017

Better physics for missiles

September 29, 2017

Concept art of enemy base

August 14, 2017

A short video on ground targets

August 14, 2017